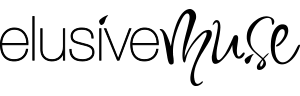

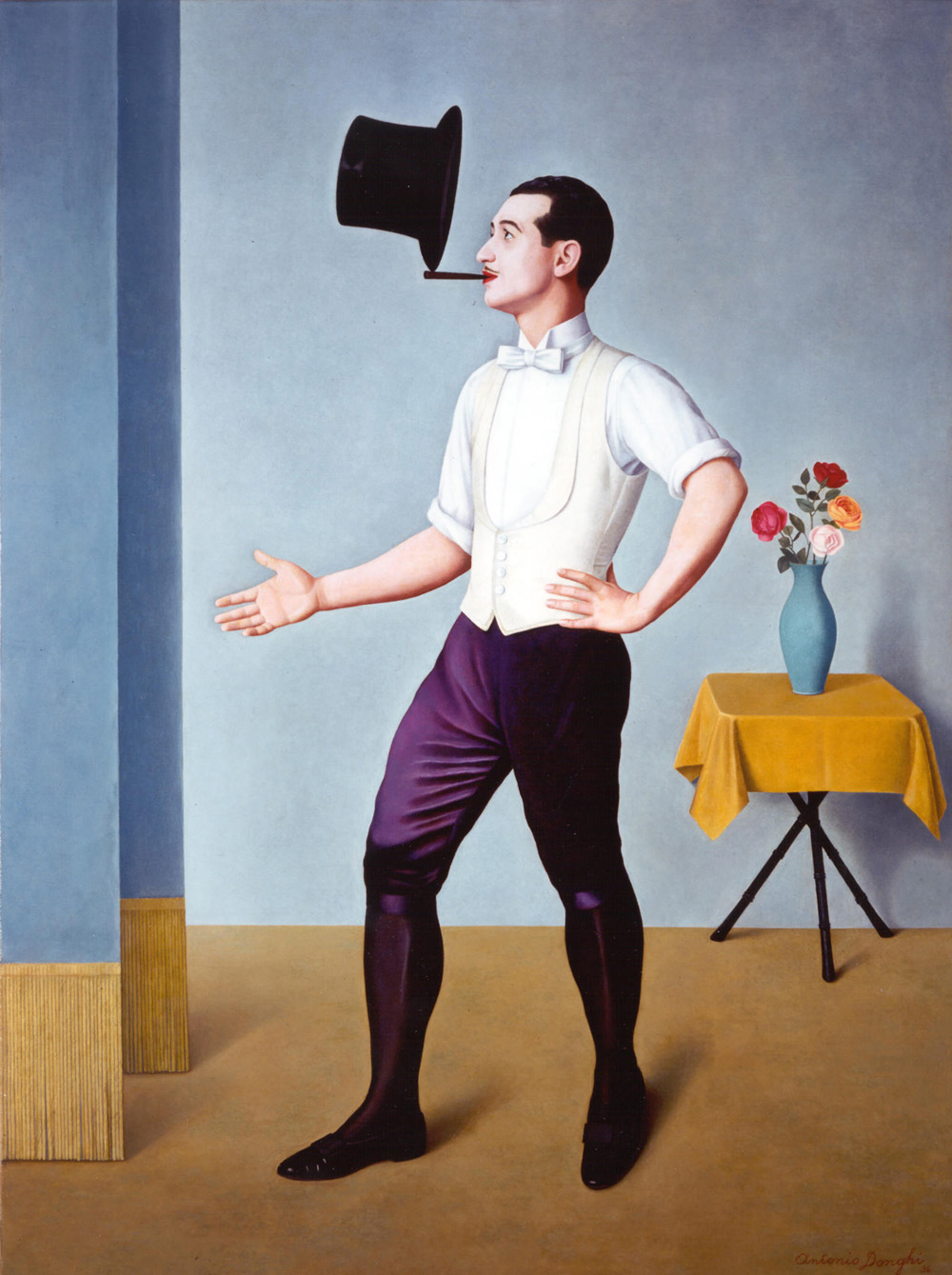

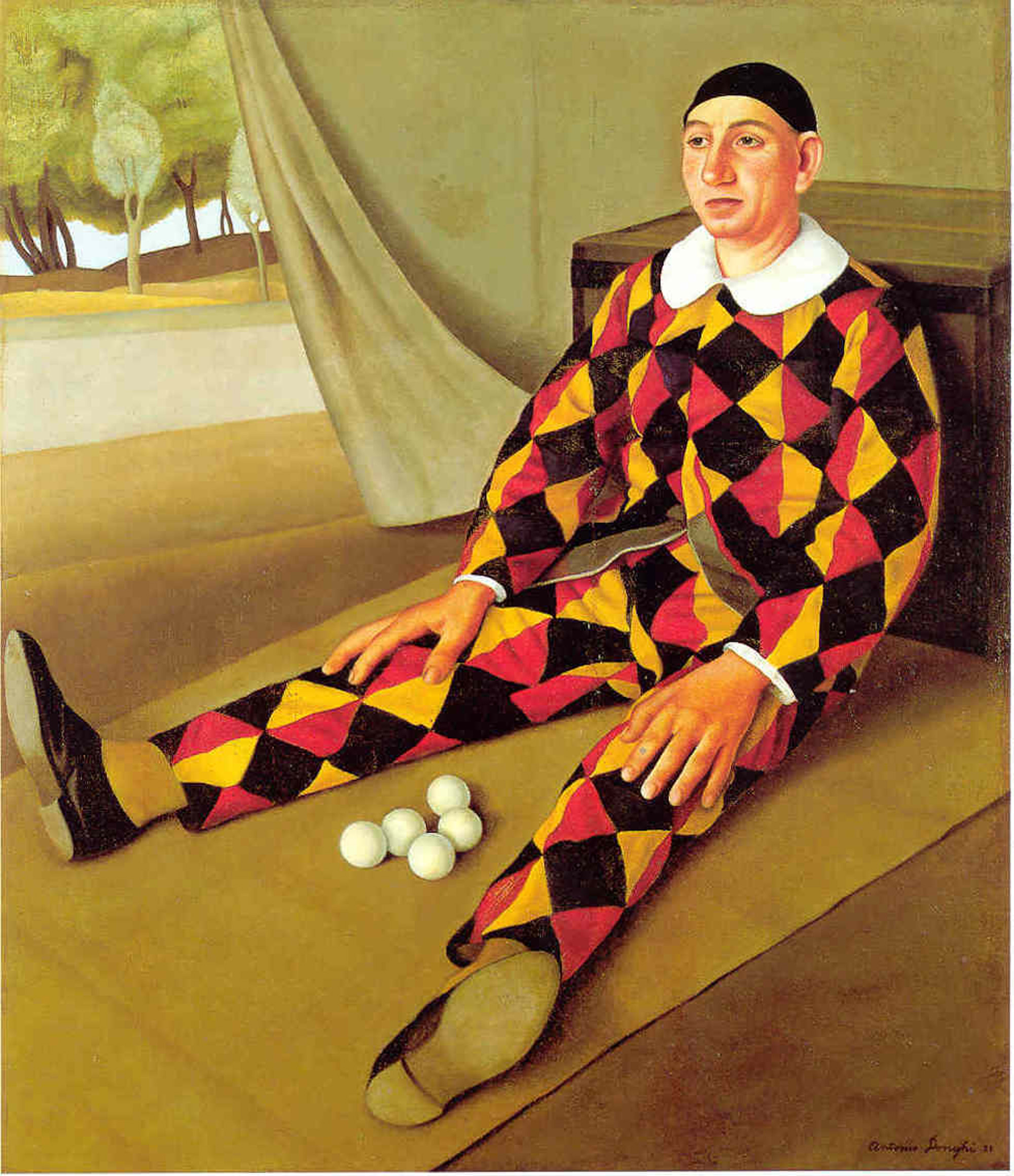

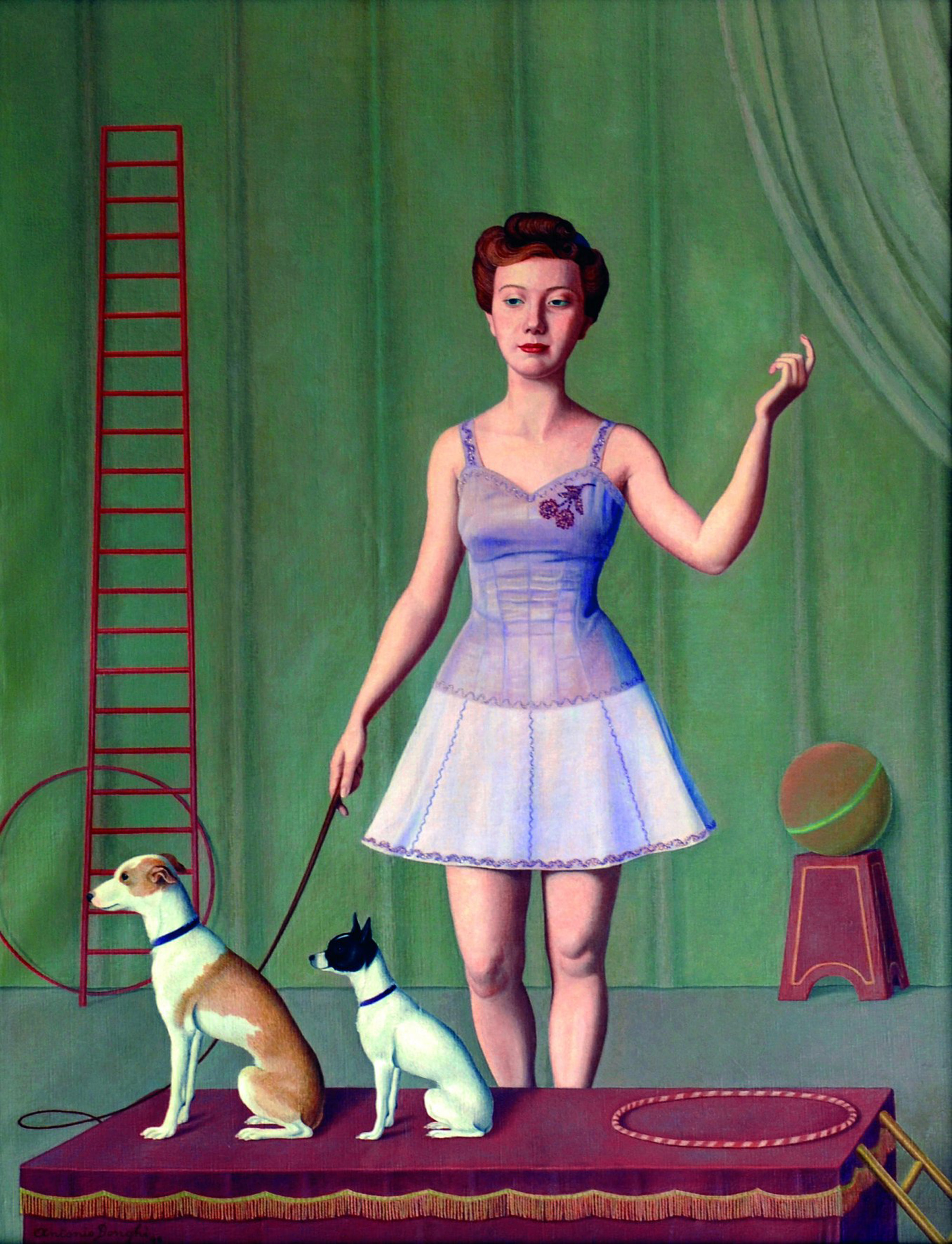

Born in Rome, Antonio Donghi studied painting at the Instituto di Belle Arti from 1908 to 1916. After military service in World War I, he studied art in Florence and Venice, soon establishing himself as one of Italy’s leading figures in the neoclassical movement that arose in the 1920s. Possessed of an extremely refined technique, Donghi favored strong composition, spatial clarity, and populist subject matter. His figures possess a gravity and an archaic stiffness reminiscent of Piero della Francesca. Critics likened his work to that of Henri Rousseau and Georges Seurat, whose scenes of contemporary life are similarly touched with a subtle humor. His still lifes often consist of a small vase of flowers, depicted with the disarming symmetry of naive art.

Donghi achieved both popular and critical success, in 1927 winning First Prize in an International Exhibit at the Carnegie Institute in Pittsburgh.

By the 1940s, Donghi’s work was far outside the mainstream of modernism, and his reputation declined, although he continued to exhibit regularly. In his last years he concentrated mainly on landscapes, painted in a style that emphasizes linear patterns. He died in Rome in 1963.

Most of Donghi’s works are in Italian collections, notably the Museo di Roma.