Hannah Höch was born Anna Therese Johanne Höch in Gotha, Germany. In 1912 she began classes at the School of Applied Arts in Berlin under the guidance of glass designer Harold Bergen. She chose the curriculum glass design and graphic arts, rather than fine arts, to please her father. In 1914, at the start of World War I, she left the school and returned home to Gotha to work with the Red Cross. In 1915 she returned to school, entering the graphics class of Emil Orlik at the National Institute of the Museum of Arts and Crafts. Also in 1915, Höch began an influential friendship with Raoul Hausmann, a member of the Berlin Dada movement. Höch’s involvement with the Berlin Dadaists began in earnest in 1917. After her schooling, she worked in the handicrafts department for Ullstein Verlag (The Ullstein Press), designing dress and embroidery patterns for Die Dame (The Lady) and Die Praktische Berlinerin (The Practical Berlin Woman). The influence of this early work and training can be seen in her later work involving references to dress patterns and textiles. From 1926 to 1929 she lived and worked in the Netherlands. Höch made many influential friendships over the years, with Kurt Schwitters and Piet Mondrian among others. Höch, along with Hausmann, was one of the first pioneers of the art form that would come to be known as photomontage.

Personal life and relationships

Art historian Maria Makela has characterized Höch’s affair with Raoul Hausmann as “stormy”, and identifies the central cause of their altercations—some of which ended in violence—in Hausmann’s refusal to leave his wife. Hausmann continually disparaged Höch not only for her desire to marry him, which he described as a “bourgeois” inclination but also for her opinions on art. Hausmann’s hypocritical stance on women’s emancipation spurred Höch to write “a caustic short story” entitled “The Painter” in 1920, the subject of which is “an artist who is thrown into an intense spiritual crisis when his wife asks him to do the dishes.”

Höch left her seven-year relationship with Raoul Hausmann in 1922. In 1926, she began a relationship with the Dutch writer and linguist Mathilda (‘Til’) Brugman, whom Höch met through mutual friends Kurt and Helma Schwitters. By autumn of 1926, Höch moved to Hague to live with Brugman, where they lived until 1929, at which time they moved to Berlin. Höch and Brugman’s relationship lasted nine years, until 1935. They did not explicitly define their relationship as a lesbian (likely because they did not feel it necessary or desirable), instead choosing to refer to it as a private love relationship. In 1935, Höch began a relationship with Kurt Matthies, whom she was married to from 1938 to 1944.

Women In Dada

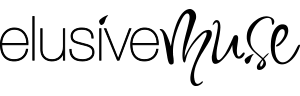

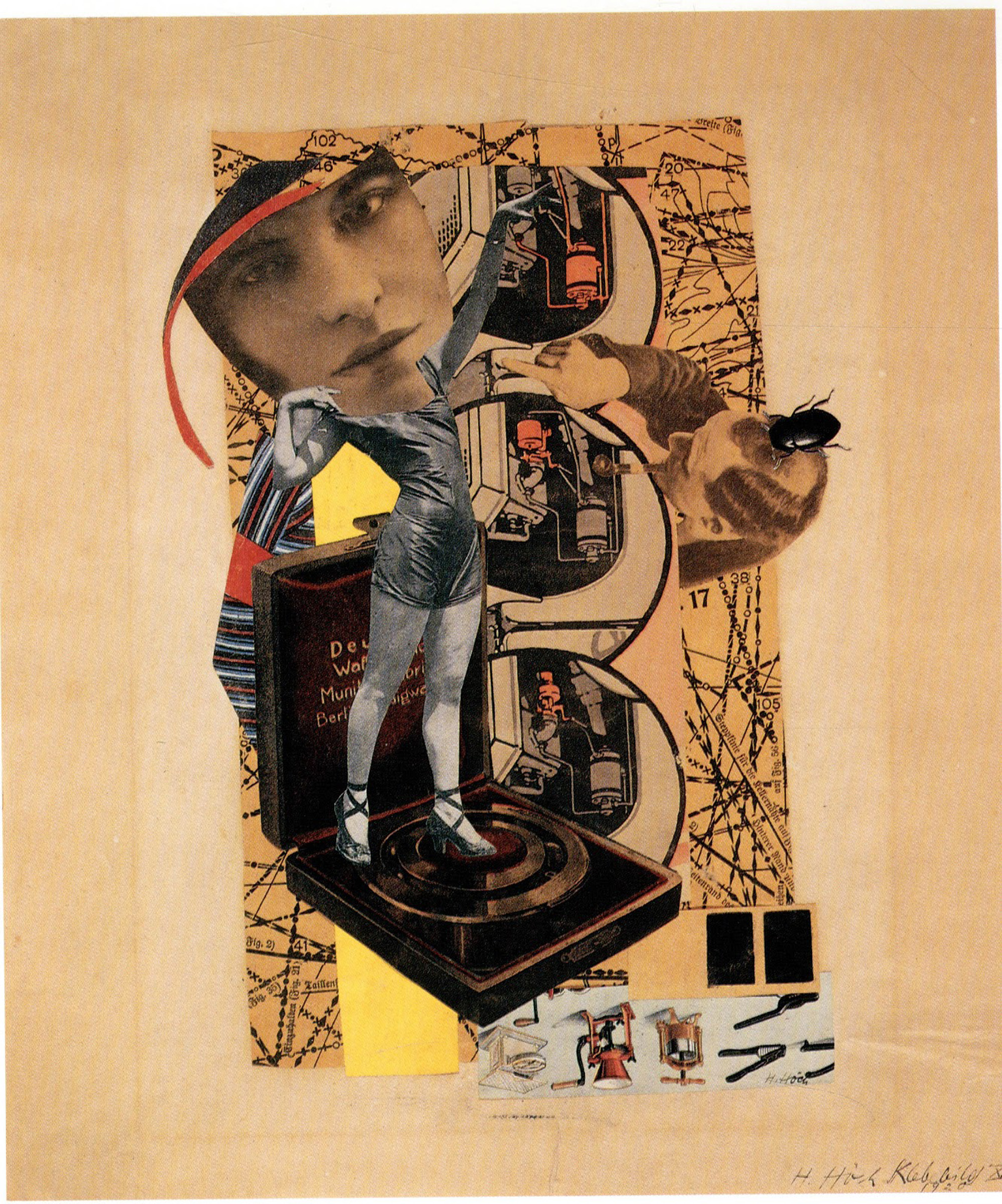

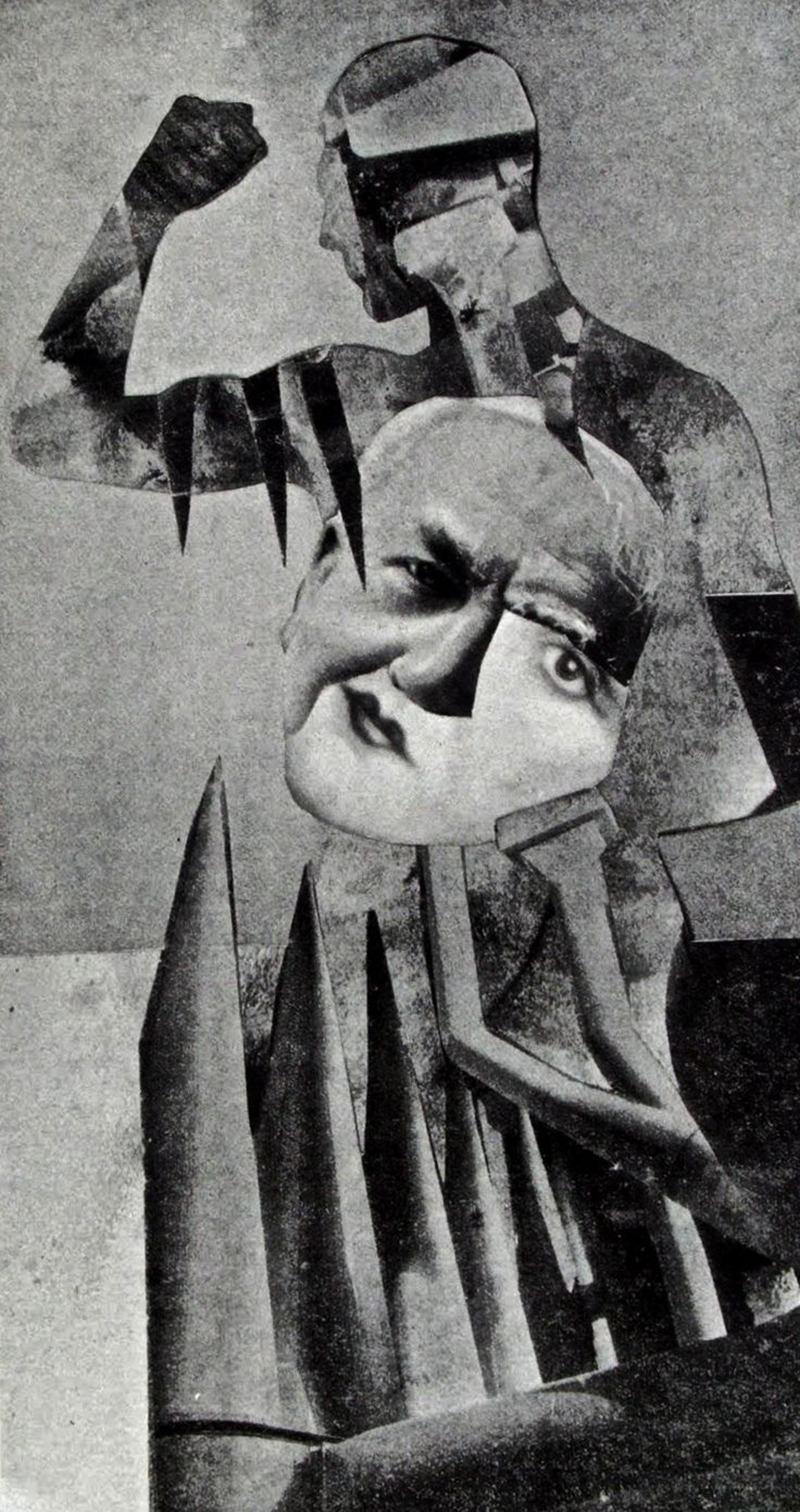

While the Dadaists, including Georg Schrimpf, Franz Jung, and Johannes Baader, “paid lip service to women’s emancipation,” they were clearly reluctant to include a woman among their ranks. Hans Richter described Höch’s contribution to the Dada movement as the “sandwiches, beer and coffee she managed somehow to conjure up despite the shortage of money.” Raoul Hausmann even suggested that Höch got a job to support him financially. Höch was the lone woman among the Berlin Dada group, although Sophie Täuber, Beatrice Wood, and Baroness Else von Freytag-Loringhoven were also important if overlooked, Dada figures. Höch references the hypocrisy of the Berlin Dada group and German society as a whole in her photomontage, Da-Dandy.

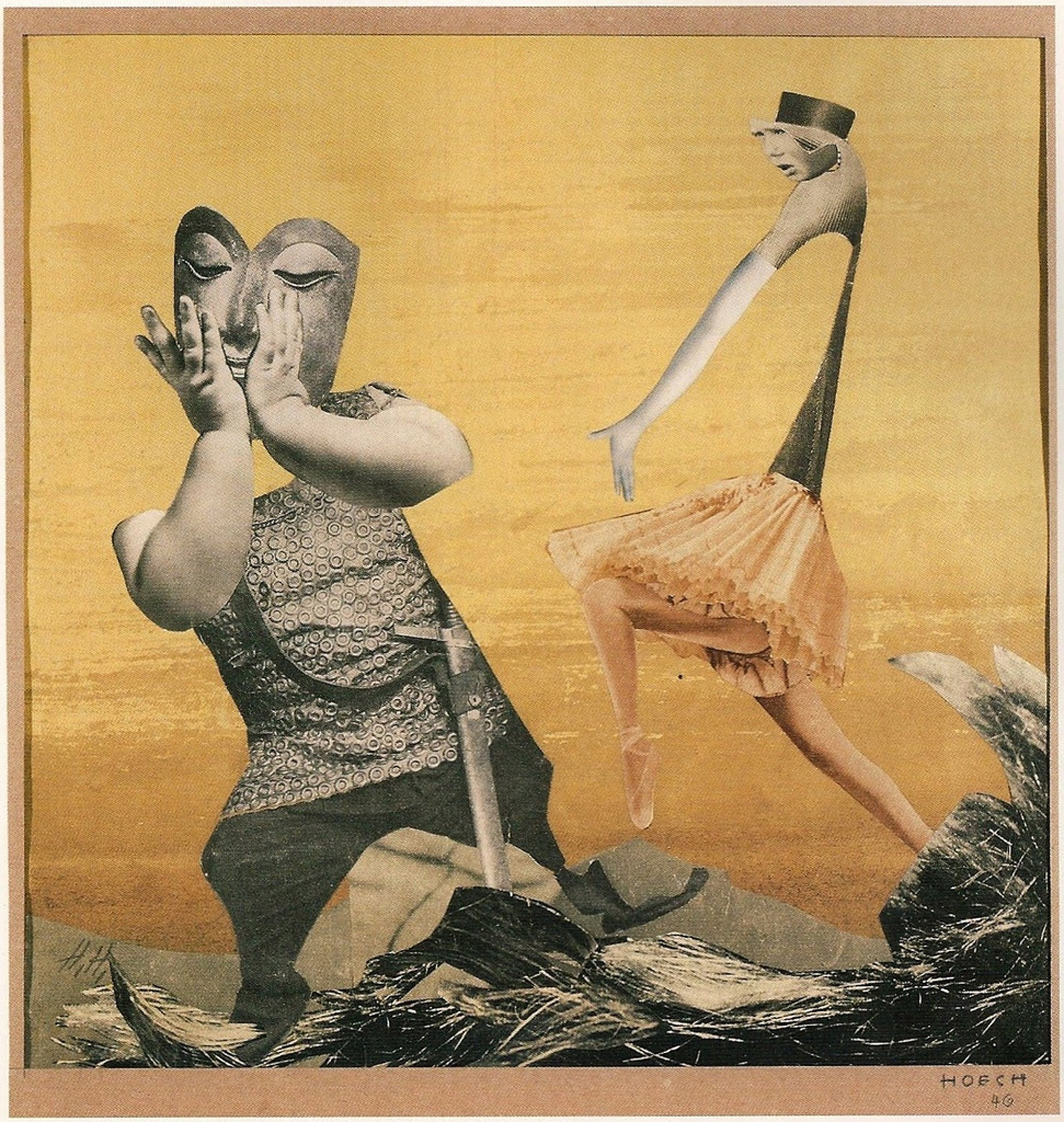

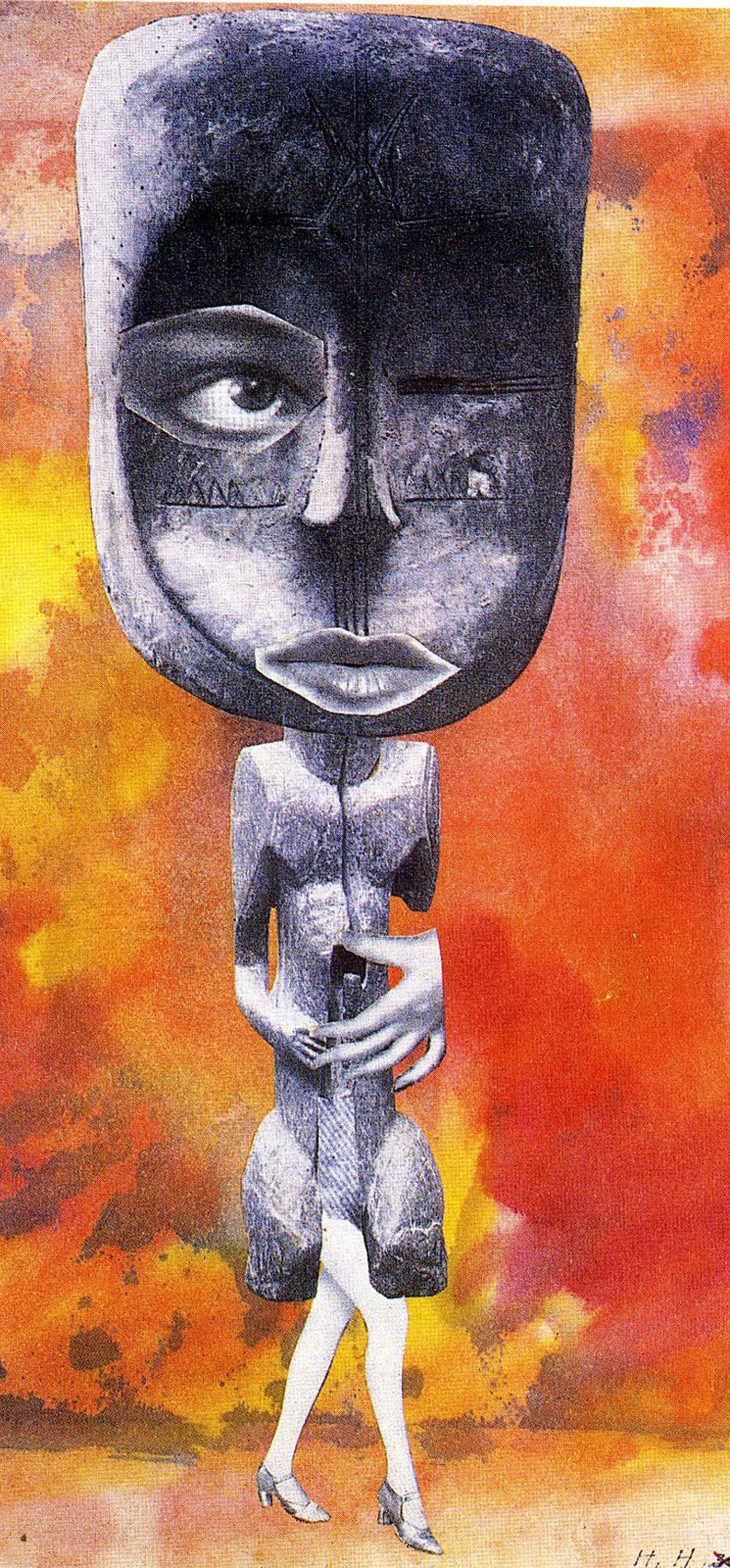

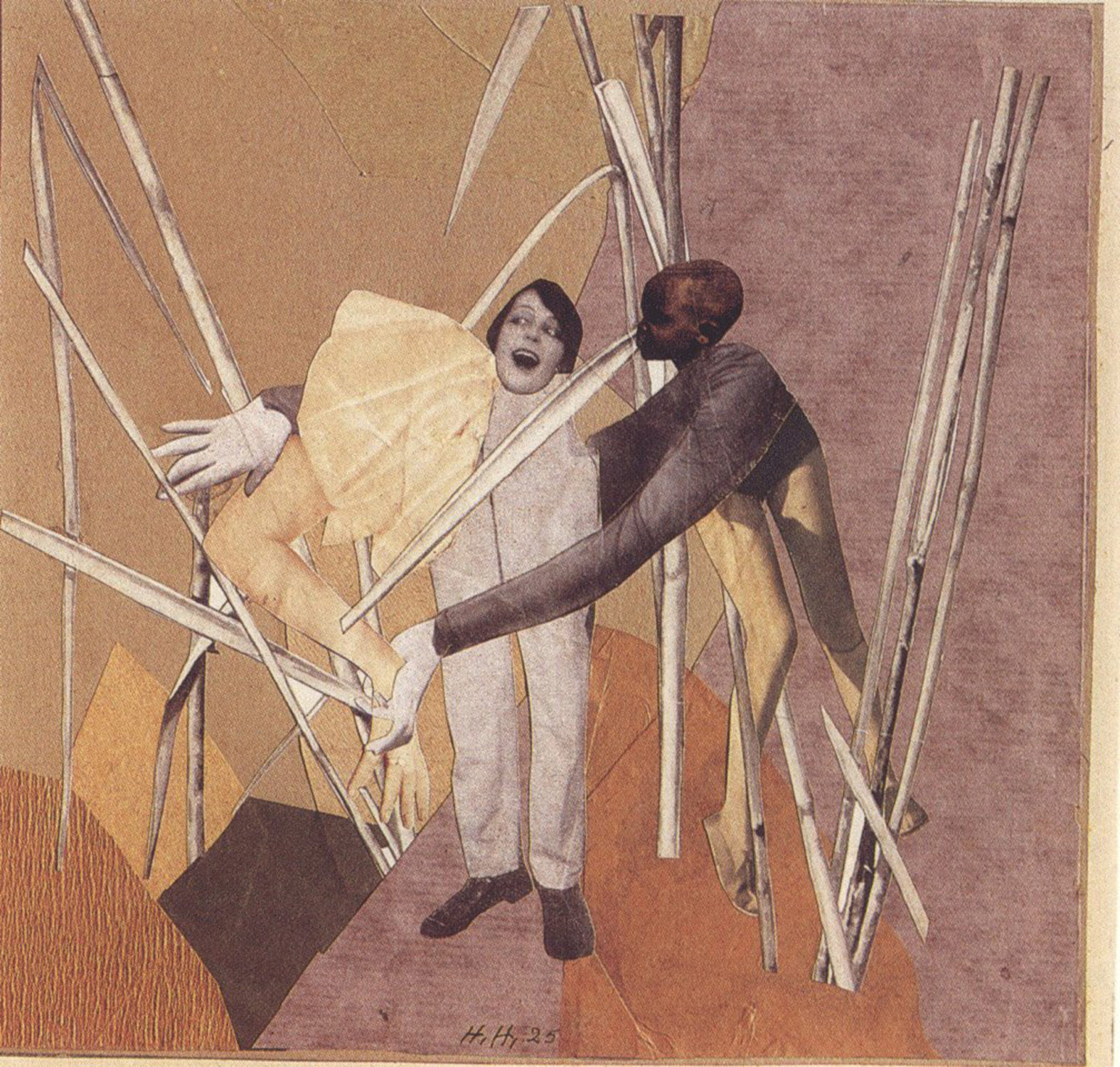

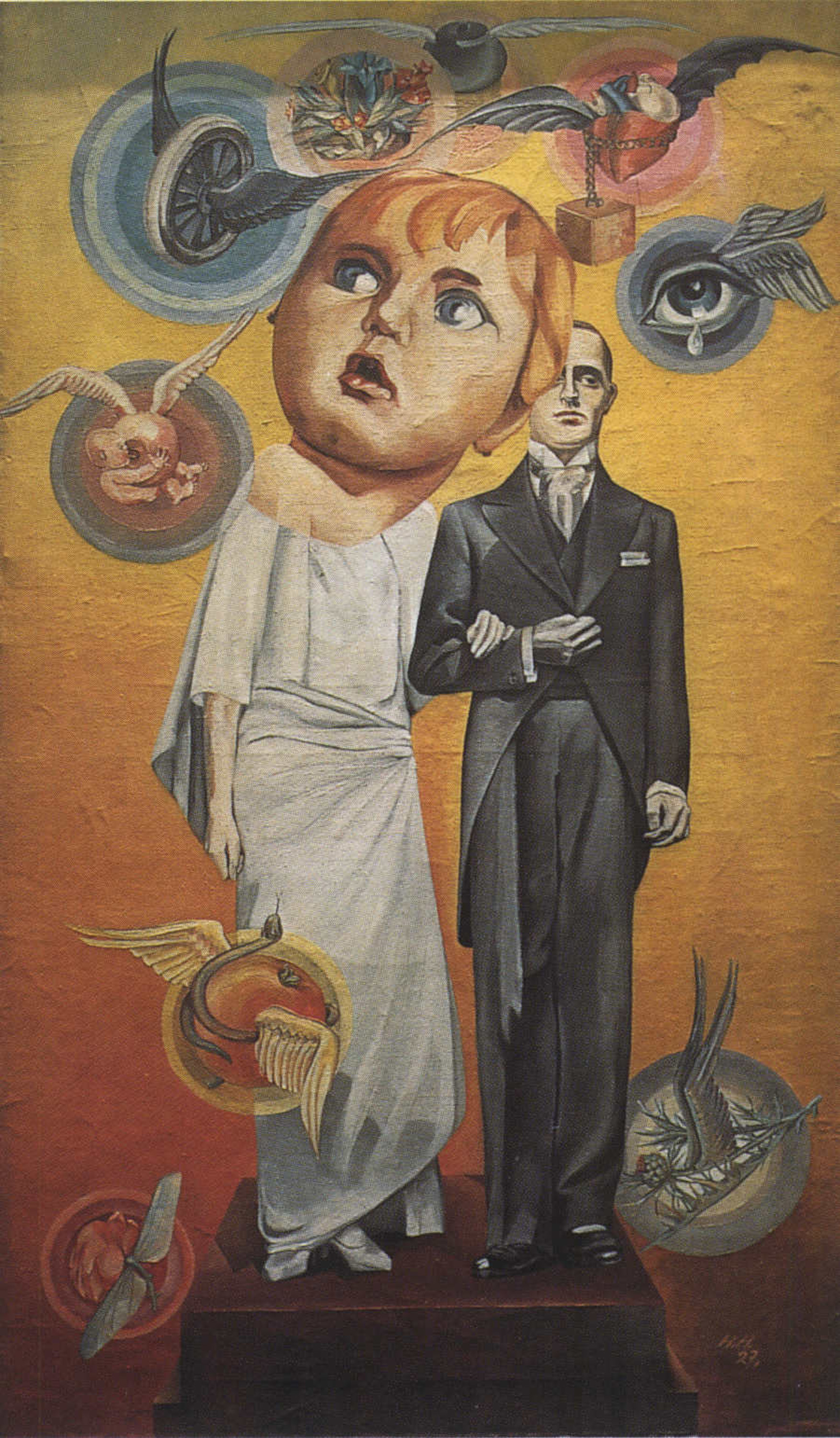

Höch’s time at Verlang working with magazines targeted to women made her acutely aware of the difference between women in media and reality, even as the workplace provided her with many of the images that served as raw material for her own work. She was also critical of marriage, often depicting brides as mannequins and children, reflecting the socially pervasive idea of women as incomplete people with little control over their lives. Höch considered herself a part of the women’s movement in the 1920s, as shown in her depiction of herself in Schnitt mit dem Küchenmesser DADA durch die letzte weimarer Bierbauchkulturepoche Deutschlands (1919–20). Her pieces also commonly combine male and female traits into one unified being. During the era of the Weimar Republic, “mannish women were both celebrated and castigated for breaking down traditional gender roles.”[10] Her androgynous characters may also have been related to her bisexuality and attraction to masculinity in women (that is, attraction to the female form paired with stereotypically masculine characteristics).

Later years

Höch spent the years of the Third Reich in Berlin, Germany, keeping a low profile. She lived in Berlin-Heiligensee, a remote area on the outskirts of Berlin, hiding in a small garden house. She married businessman and pianist Kurt Matthies in 1938 and divorced him in 1944. Though her work was not acclaimed after the war as it had been before the rise of the Third Reich, she continued to produce her photomontages and exhibit them internationally until her death in 1978, in Berlin. Her house and garden can be visited at the annual Day of the Memorial.

It’s going to be finish of mine day, but before finish, I am reading this wonderful piece

of information, to improve my knowledge.

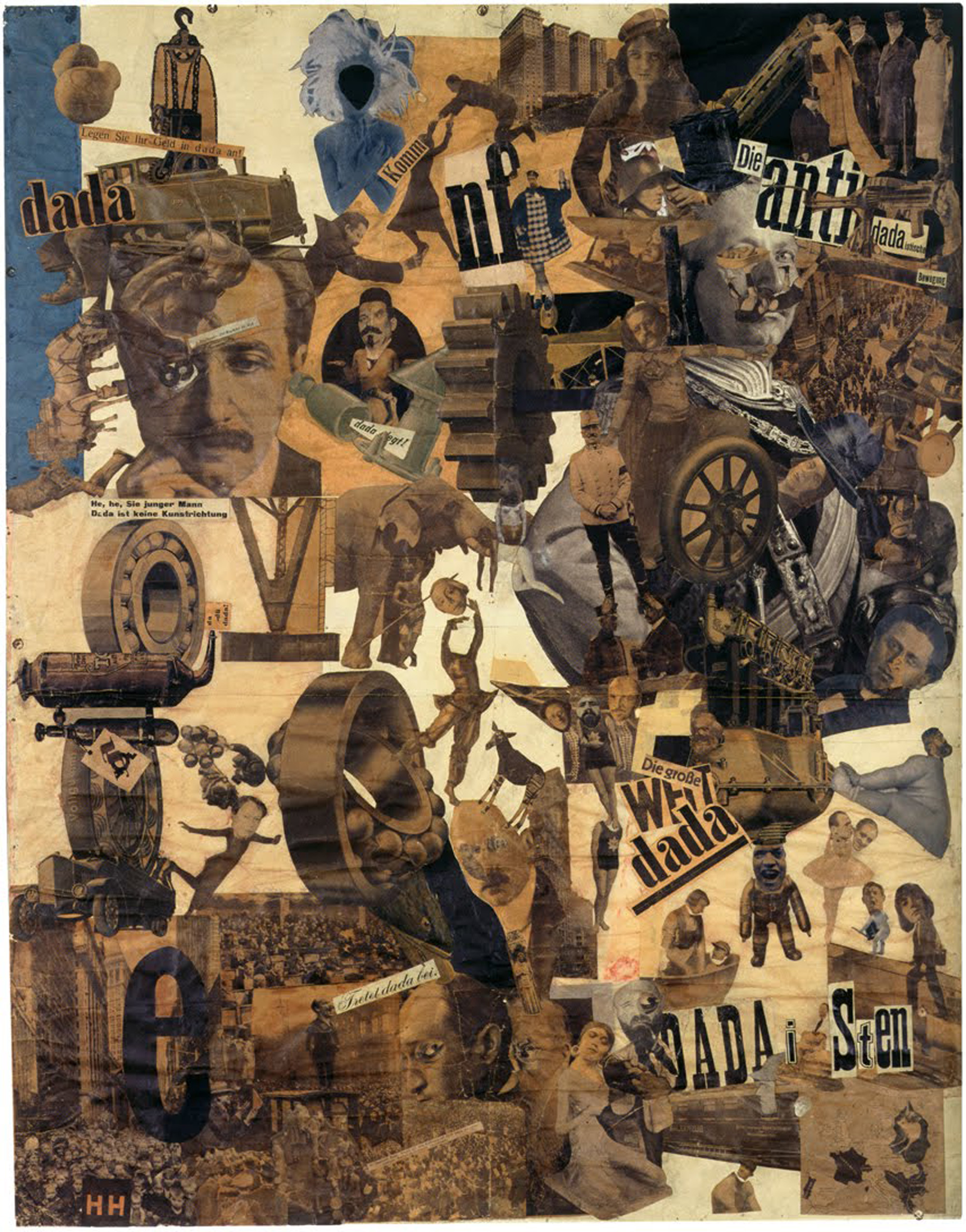

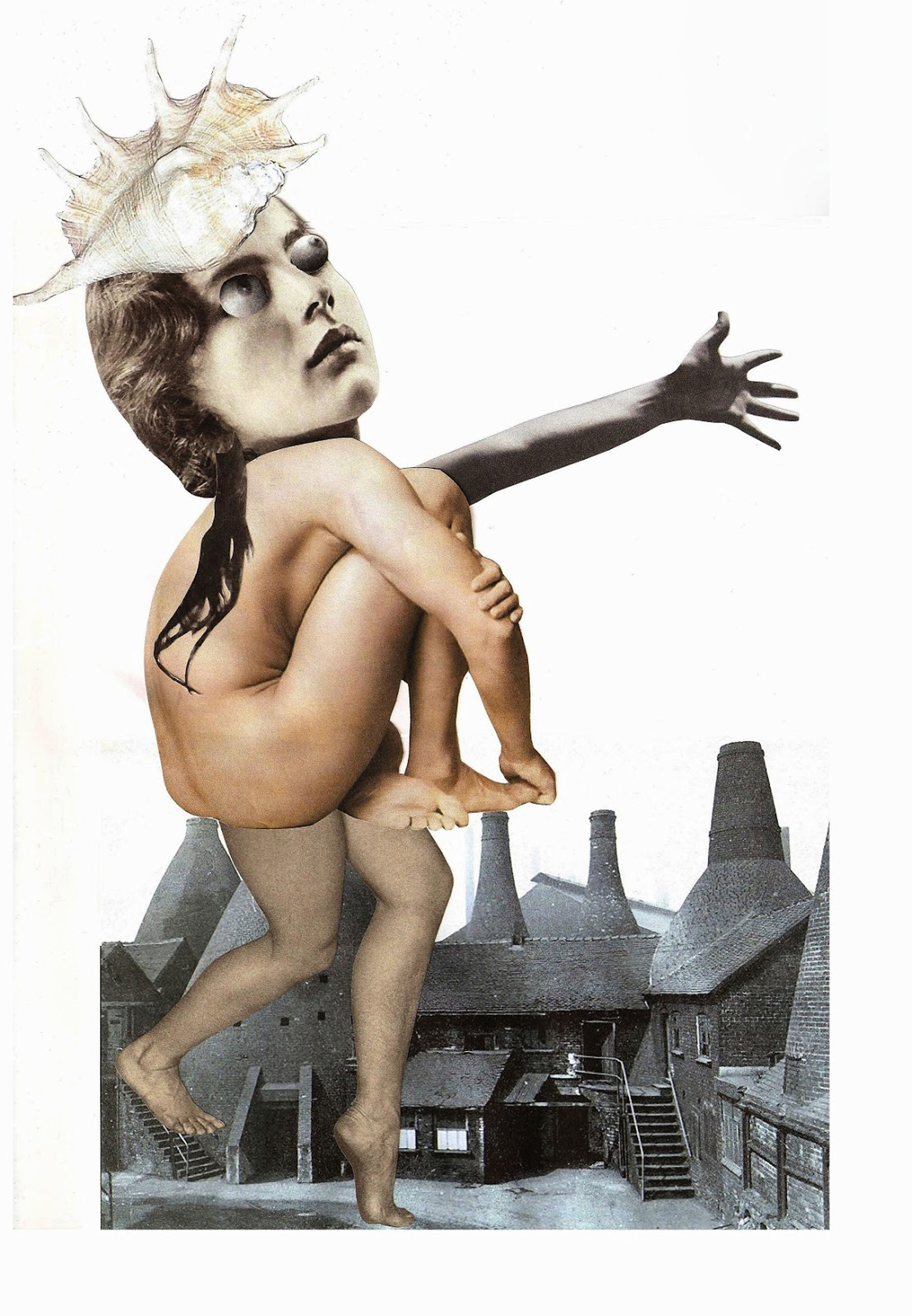

[…] Hannah Höch was a German Dada artist she was one of the originators of photomontage. She drew her inspiration from the collage work of Pablo Picasso and Kurt Schwitters. Much like László Moholy-Nagy, Hannah Höch uses a lot of muted colours, though she does tend to use brighter coloured backgrounds these seem to often be the only or limited source of colour within her works. She uses a layering technique to create her pieces and prefers to use metaphors rather then stating it in text, she often include collages of people that have impossible proportions or look inhuman, prompting the question within her pieces of ‘what is beauty?’ and questioning the different beauty standards around the world. She focused her criticism on gender issues and challenged the traditional domestic role of females, she became recognized as a pioneering feminist artist. She was introduced by Raoul Haussman to Dadaism, this is a artistic movement that began in Zurich in response to World War I and carried political overtones that dominated the pieces. (The Daily Muse: Hannah Höch (1889 – 1978), Photomontage/Collage Artist – elusivemu.se, 2020) […]