Sol LeWitt earned a place in the history of art for his leading role in the Conceptual movement. His belief in the artist as a generator of ideas was instrumental in the transition from the modern to the postmodern era. Conceptual art, expounded by LeWitt as an intellectual, pragmatic act, added a new dimension to the artist’s role that was distinctly separate from the romantic nature of Abstract Expressionism. LeWitt believed the idea itself could be the work of art, and maintained that, like an architect who creates a blueprint for a building and then turns the project over to a construction crew, an artist should be able to conceive of a work and then either delegate its actual production to others or perhaps even never make it at all. LeWitt’s work ranged from sculpture, painting, and drawing to almost exclusively conceptual pieces that existed only as ideas or elements of the artistic process itself.

Key Ideas

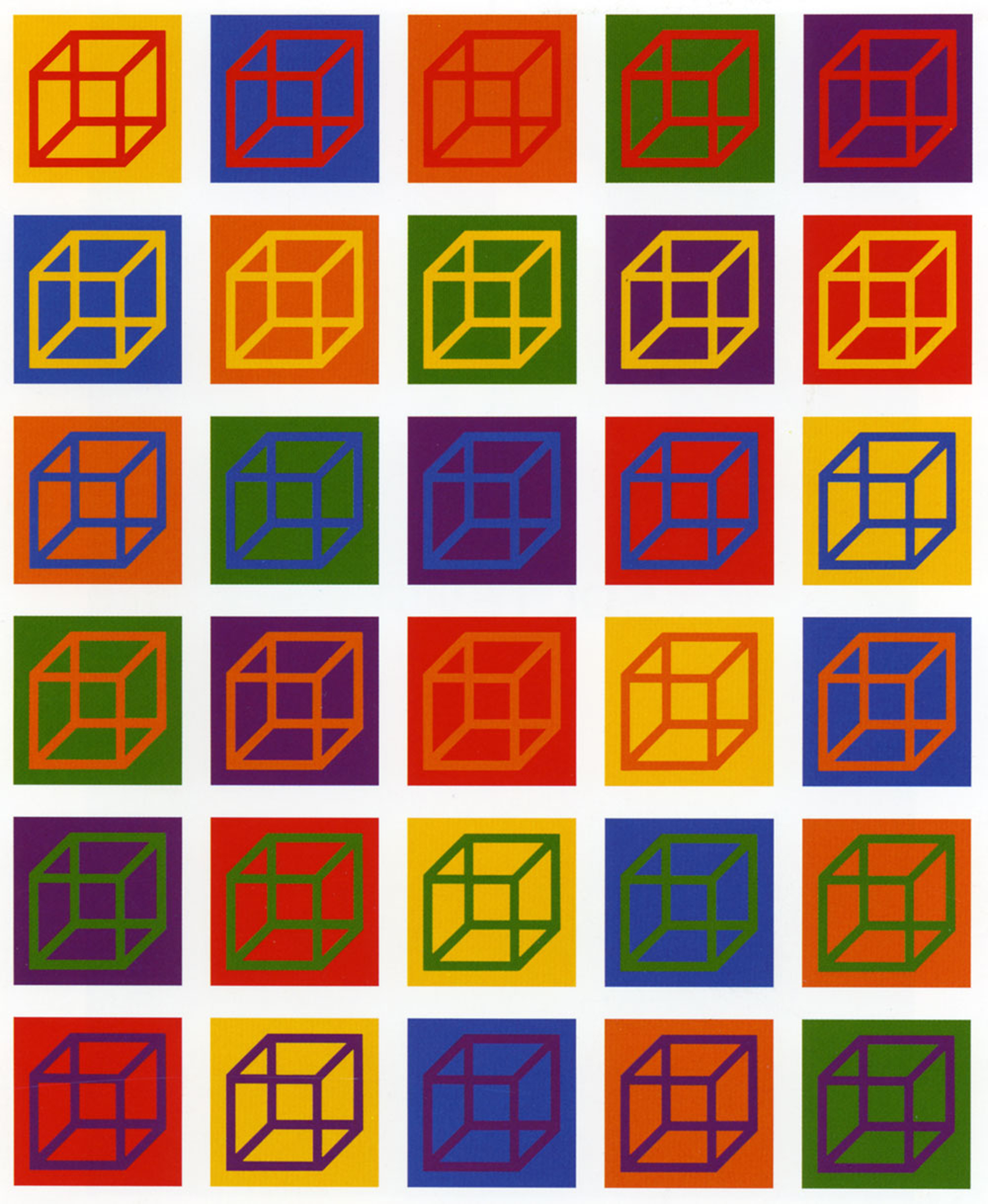

LeWitt’s refined vocabulary of visual art consisted of lines, basic colors, and simplified shapes. He applied them according to a formula of his own invention, which hinted at mathematical equations and architectural specifications, but were neither predictable nor necessarily logical. For LeWitt, the directions for producing a work of art became the work itself; a work was no longer required to have an actual material presence in order to be considered art.

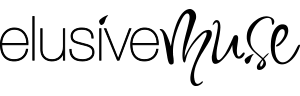

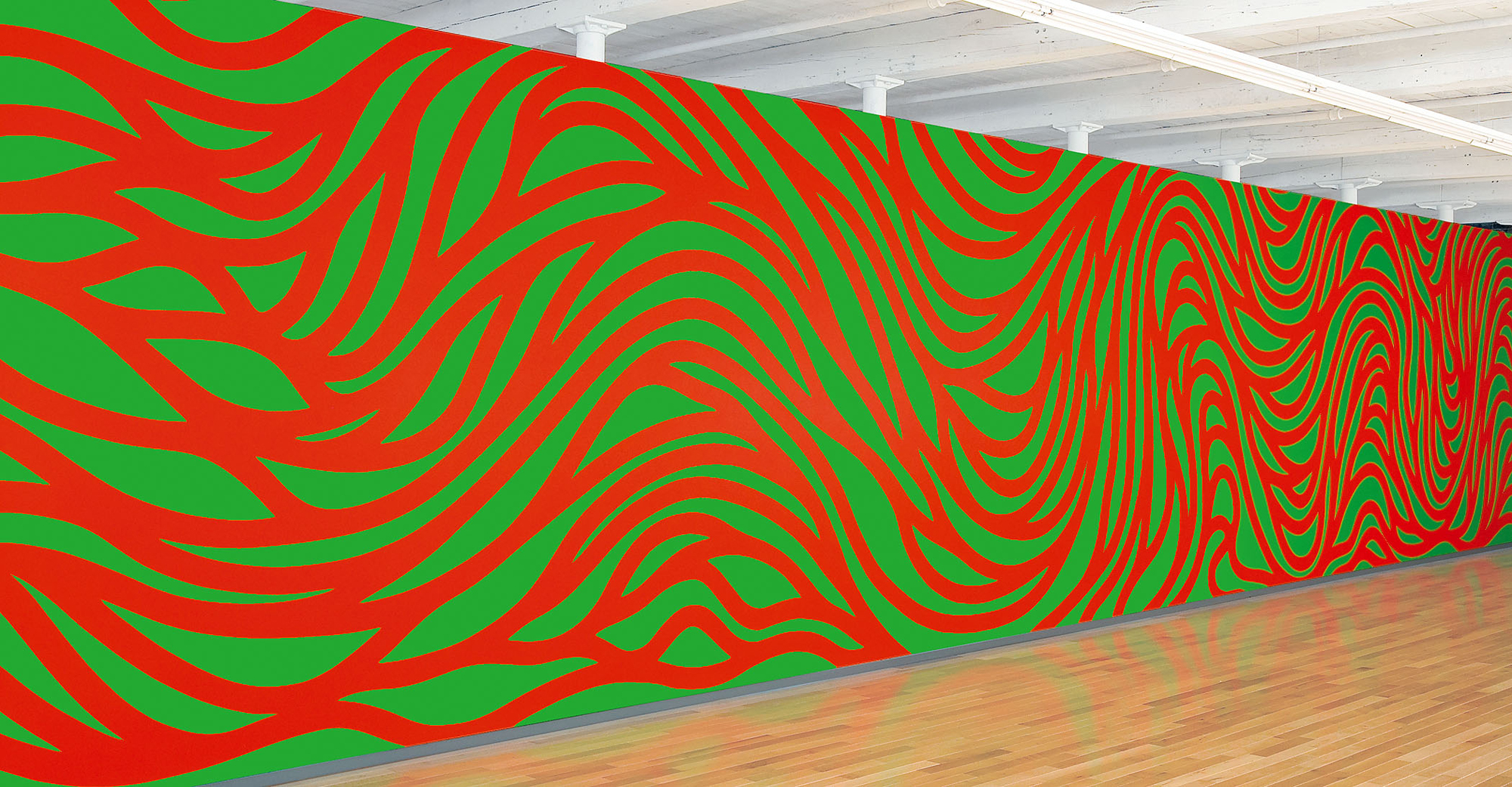

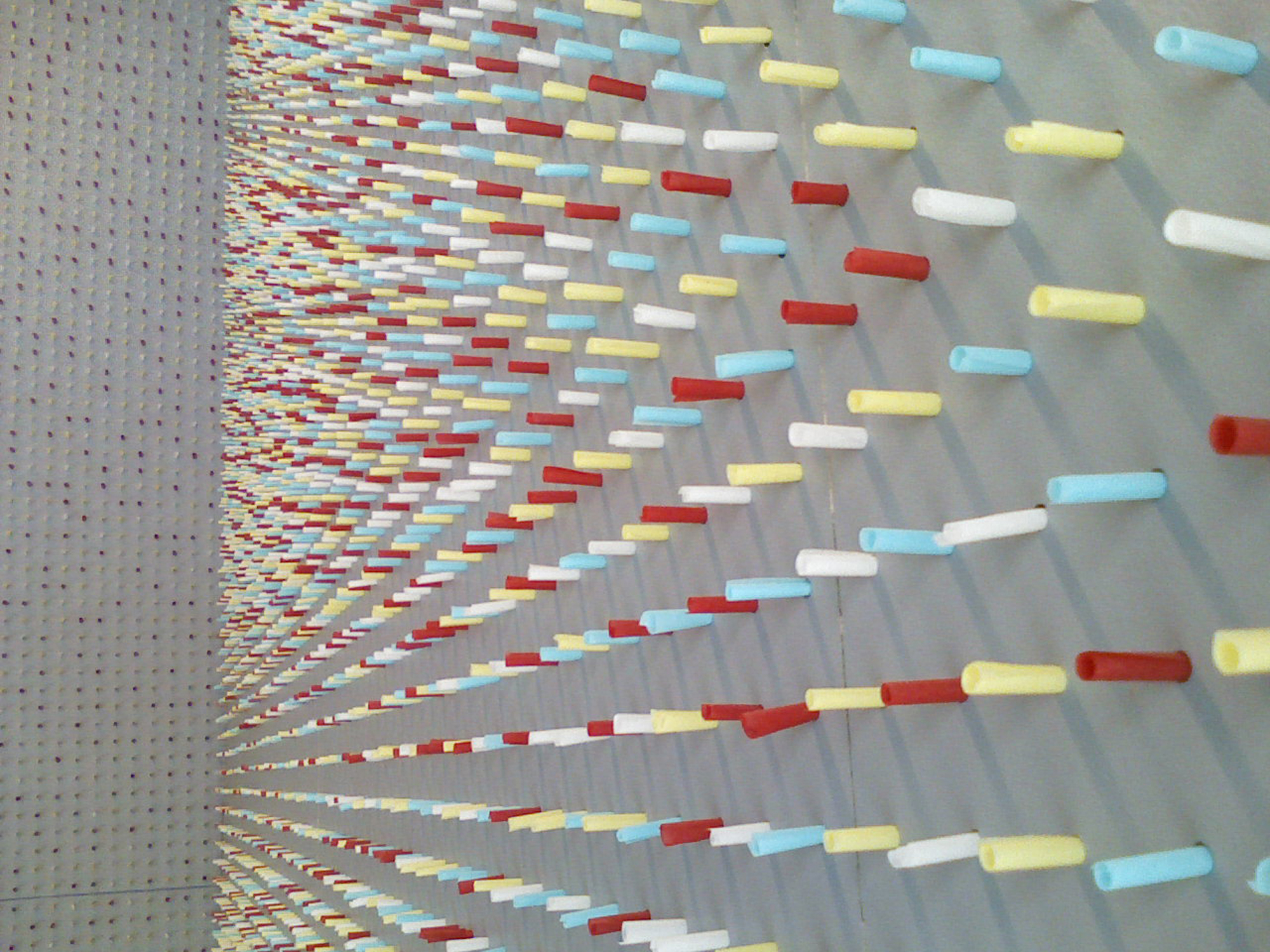

LeWitt’s conceptual pieces often did take on at least basic material form, although not necessarily at his own hands. In the spirit of the medieval workshop in which the master conceives of a work and apprentices carry out his instructions based on preliminary drawings, LeWitt would provide an assistant or a group of assistants with directions for producing a work of art. Instructions for these works, whether large-scale wall drawings or outdoor sculptures, were deliberately vague so that the end result was not completely controlled by the artist that conceived the work. In this way, LeWitt challenged some very fundamental beliefs about art, including the authority of the artist in the production of a work. His emphasis is most often on process and materials (or the lack thereof in the case of the latter) rather than on imbuing a work with a specific message or narrative. Art, for LeWitt, could exist for its own sake. Meaning was not a requirement.

Whereas many Minimalist artists turned to industrial materials, LeWitt simplified even further, still employing traditional materials – wood, canvas, paint, for instance – but focusing instead on concepts and systems. While the use of industrial materials implied a certain expectation of permanence with regard to a work of art, in direct contrast, LeWitt appreciated the ephemeral character and impermanence of Conceptual art. In short, he let the traditional materials speak for themselves, to demonstrate their own vulnerability to decay, destruction, or obsolescence.

We think to small. Let’s move on to large scale installations.

And I was excited to start my very first ‘large’ piece – 18 x 18. Compared to this it is like working on a postage stamp 🙂

Inspiring, thanks for sharing.

Amazing!